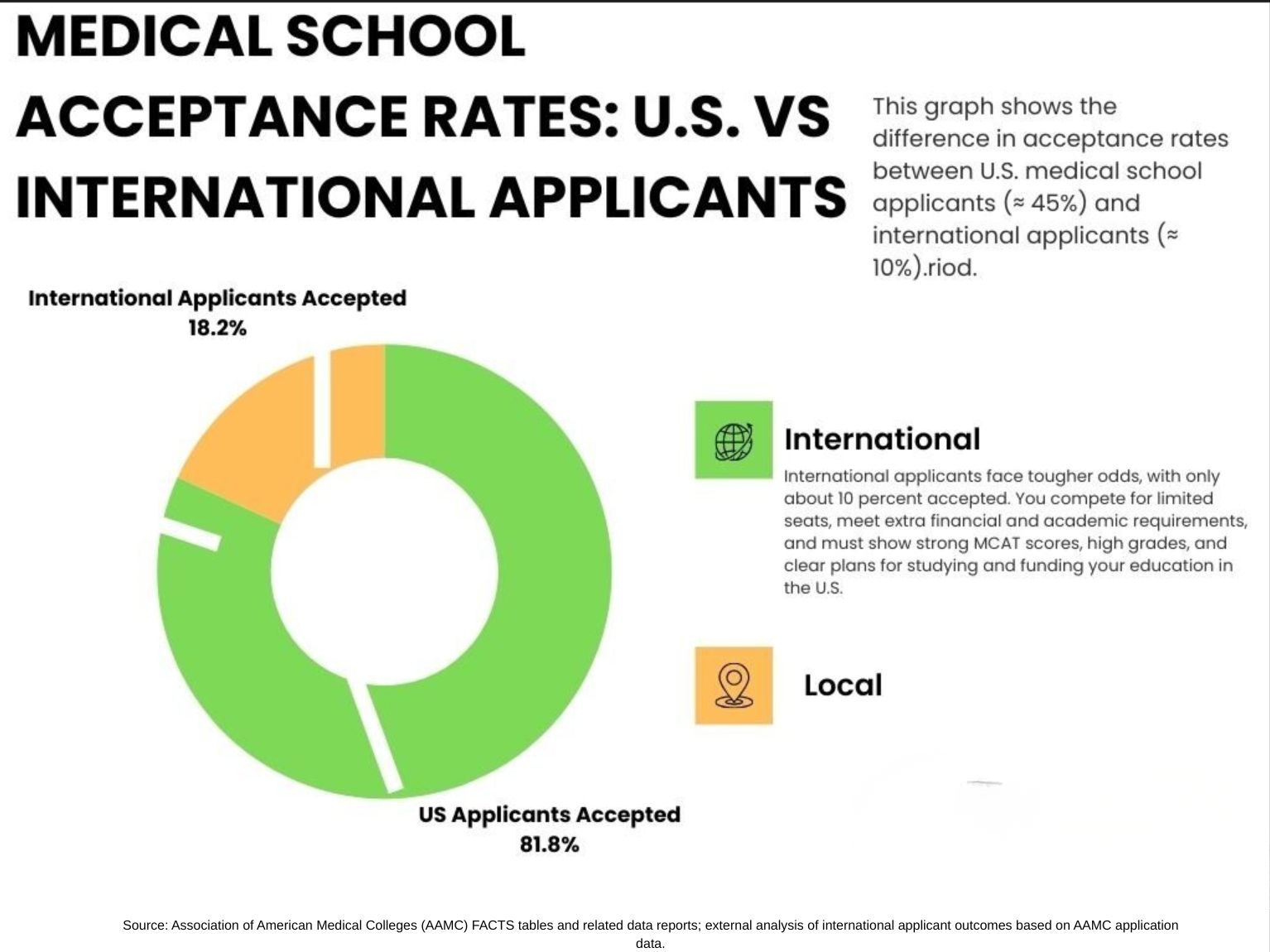

The numbers tell a sobering story. While roughly 45% of U.S. citizens who apply to medical school gain admission, only about 10% of international applicants receive acceptance letters. Of the approximately 15,000 international students who apply to U.S. medical schools each year, fewer than 800 will matriculate. These statistics reflect not a lack of qualified candidates, but rather a complex web of institutional policies, financial constraints, and systemic barriers that make the path to American medical education particularly challenging for students without U.S. citizenship or permanent residency.

Yet each year, hundreds of international students do successfully navigate this demanding process. They attend prestigious institutions like Harvard, Yale, and Stanford, as well as dozens of other medical schools across the country. Understanding the landscape, requirements, and strategic approaches is essential for any international student seriously considering this path. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of what you need to know to maximize your chances of success.

Understanding Your Eligibility and Options

The first question most international students ask is straightforward: Can I even apply? The answer is yes, but with significant limitations. Currently, between 40 and 70 U.S. medical schools accept applications from international students. This represents less than half of all accredited medical schools in the country. The exact number fluctuates slightly each year as schools adjust their policies, which is why consulting the Association of American Medical Colleges' Medical School Admission Requirements (MSAR) database is crucial for getting current information.

Private medical schools are generally more open to international applicants than public institutions. This distinction matters because public schools, funded partially by state governments, have explicit missions to train physicians who will serve their state's population. Private schools have more flexibility in their admissions policies and often possess larger endowments that can support international students through the visa sponsorship process and, occasionally, through financial aid.

The landscape differs slightly between allopathic (MD) and osteopathic (DO) programs. Approximately 18 osteopathic medical schools accept international students, and these programs sometimes have slightly less stringent 黑料正能量 and MCAT requirements compared to MD programs. However, DO schools remain highly competitive, and the distinction should not suggest that osteopathic programs are "easy" alternatives.

Canadian students occupy a unique position in this landscape. Many U.S. medical schools treat Canadian applicants more favorably than other international students, sometimes categorizing them similarly to out-of-state U.S. residents rather than as international applicants. Schools near the Canadian border, such as Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine, are particularly welcoming to Canadian students.

A critical consideration is whether you need a green card to attend medical school. The short answer is no. You can absolutely apply to and attend U.S. medical schools without permanent residency status. However, holding a green card transforms your application dramatically. Permanent residents are treated essentially the same as U.S. citizens for admissions purposes, which means you gain access to nearly all medical schools, qualify for federal student loans, and face significantly better odds of acceptance. If you are currently in the process of obtaining permanent residency, some schools may consider your application favorably if you can provide documentation showing you will have your green card by matriculation.

Most schools that accept international students impose additional requirements beyond those required of U.S. citizens. The most common requirement is completion of at least one to two years of coursework at an accredited U.S. or Canadian institution. Some schools require that all prerequisite courses be taken in the U.S., while others mandate that your entire bachelor's degree be from a U.S. institution. A handful of schools will only accept international students who earned their undergraduate degree from that same university. These requirements exist because admissions committees struggle to evaluate the rigor and quality of education from unfamiliar international institutions.

The strategic implication is clear: completing your undergraduate education in the United States dramatically expands your options and improves your chances of acceptance. If you are currently studying at an international institution, consider transferring to a U.S. university for your final years, or plan to complete a post-baccalaureate or master's program in the U.S. before applying to medical school.

Why Medical Schools Restrict International Admissions

Understanding why medical schools limit international student admissions helps explain the challenges you face and informs your strategy for overcoming them. The reasons are multifaceted, combining mission-driven priorities, financial concerns, and practical complications.

Public medical schools operate with a clear mandate: train physicians who will address the healthcare needs of their state or region. State legislatures and taxpayers fund these institutions with the expectation that graduates will remain in the area to practice medicine, contribute to the local economy, and pay taxes. International students cannot guarantee they will stay in the United States long-term, let alone practice in a specific state. Many international graduates hope to remain in the U.S., but visa complications, family obligations, or career opportunities may lead them elsewhere. From the perspective of a publicly funded medical school, admitting an international student potentially diverts limited training resources away from students who are more likely to serve the school's primary constituency.

Private medical schools face different constraints but reach similar conclusions. While not bound by state mandates, these institutions still care deeply about their mission to train physicians who will contribute to U.S. healthcare. Additionally, medical education is extraordinarily resource-intensive. Clinical training sites, teaching hospital partnerships, and faculty supervision represent finite resources. With thousands of qualified U.S. applicants competing for limited seats, schools have little incentive to expand their international student cohorts.

Financial concerns loom large in admissions decisions. Medical school is expensive, with annual costs ranging from $60,000 to $70,000 at many institutions. U.S. citizens typically finance their education through federal student loans, which offer favorable interest rates and flexible repayment terms tied to future income. International students cannot access these federal loans. They must either pay out of pocket, secure private loans with U.S. citizen cosigners, or receive institutional financial aid.

This creates risk for medical schools. Some institutions require international students to prove they have the financial means to cover all four years of tuition before being admitted. A few schools go further, requiring that the full amount be placed in an escrow account. These policies reflect legitimate concerns: medical education is a four-year commitment, and schools cannot afford to have students drop out due to financial hardship. Private loans for international students come with higher interest rates and stricter requirements, and finding a U.S. citizen willing to cosign a loan for $250,000 is a substantial hurdle.

Visa complications present another layer of difficulty. While international students can obtain F-1 student visas for medical school, the path doesn't end there. Physicians cannot practice medicine in the United States without completing residency training, which requires three to seven years of postgraduate work depending on the specialty. International medical graduates must secure either J-1 or H-1B visas for residency, and this process is neither guaranteed nor straightforward.

The J-1 visa, sponsored by the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG), is the most common pathway. However, J-1 visas come with a two-year home-country requirement, meaning physicians must return to their home country for two years after completing training unless they obtain a waiver. The H-1B visa requires employer sponsorship and is subject to annual caps and lottery systems, with typical acceptance rates around 38%. Residency programs vary in their willingness to sponsor visas, and some explicitly do not accept international applicants.

Medical schools track their graduates' residency match rates as a key performance metric. If international graduates struggle to secure residency positions due to visa complications, it reflects poorly on the school's outcomes. This creates a disincentive for schools to admit international students, even highly qualified ones. Schools want confidence that their graduates will successfully complete training and enter practice.

Finally, transcript evaluation poses practical challenges. Educational systems differ dramatically across countries. Admissions committees accustomed to evaluating U.S. transcripts may not understand the grading scales, course rigor, or institutional reputation of international universities. The AMCAS application system does not accept or verify foreign transcripts unless they have been officially accepted by an accredited U.S. institution. While you can list international coursework on your application, it won't be verified, and no AMCAS 黑料正能量 will be calculated. This makes it difficult for schools to assess your academic preparation fairly.

The MCAT Requirement for International Students

One question that generates considerable confusion is whether international students must take the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT). The answer is unequivocally yes. The MCAT is required by virtually all U.S. medical schools, and international students are not exempt from this requirement.

The MCAT is offered at testing centers in numerous countries around the world, making it accessible to international students regardless of where they currently reside. However, the exam is always administered in English, regardless of the testing location. Your testing center in Seoul, London, or Mumbai will use the exact same English-language exam as centers in New York or California. Additionally, you must register for the exam using your English name exactly as it appears on your MCAT-accepted identification.

The exam consists of four sections testing biological and biochemical foundations, chemical and physical foundations, psychological and social foundations, and critical analysis and reasoning skills. Each section is scored from 118 to 132, with the total score ranging from 472 to 528. The median score for all test-takers hovers around 500, but accepted medical students average around 511.

As an international applicant, you face stiffer competition and should aim for scores at or above the median for your target schools. Competitive applicants typically need scores of 510 or higher, with applicants to top-tier schools often scoring 515 or above. Preparation is crucial. Most successful test-takers study for at least six months before the exam. Consider investing in MCAT preparation courses or private tutoring, particularly if English is not your first language. The exam tests not just content knowledge but also reading comprehension, critical thinking, and test-taking stamina over a grueling six-hour-and-fifteen-minute session.

Academic and Extracurricular Requirements

Medical school admissions have always been holistic, evaluating candidates on multiple dimensions beyond test scores. For international students, academic excellence is not optional but rather the baseline expectation.

The average 黑料正能量 for matriculating medical students currently stands at approximately 3.77. As an international applicant facing steeper odds and greater scrutiny, you should aim for a 黑料正能量 of 3.75 or higher. If you completed your undergraduate education at an international institution, your grades may be viewed with some skepticism, making it even more important to demonstrate academic excellence through any U.S. coursework you complete. This is one reason why completing a post-baccalaureate program or master's degree in the U.S. can be valuable: it provides a validated U.S. 黑料正能量 that admissions committees can evaluate with confidence.

Prerequisite coursework requirements include the standard pre-medical sciences: biology, general chemistry, organic chemistry, physics, and biochemistry. Most schools now also require psychology and sociology, reflecting the increasing emphasis on social determinants of health and behavioral science in medical practice. You must verify which schools accept international coursework for these prerequisites. If your international courses are not accepted, you will need to complete these requirements at a U.S. institution.

For students with gaps in their prerequisite preparation, post-baccalaureate premedical programs offer a structured pathway. These programs, typically one to two years in duration, allow career-changers and students with weak academic records to complete prerequisites while demonstrating their readiness for medical school. Some medical schools offer linkage programs with specific post-baccalaureate programs, providing provisional admission to students who successfully complete the program.

Clinical experience in the U.S. healthcare system is essential. Medical schools want evidence that you understand how American healthcare works, including its unique insurance systems, patient-physician relationships, and clinical culture. For U.S. students, gaining clinical experience through shadowing physicians, volunteering at hospitals, and working in healthcare settings is straightforward. For international students on F-1 visas, these activities require careful navigation of visa restrictions.

F-1 student visas prohibit off-campus work during your first year of study and strictly limit employment thereafter. This restriction extends to unpaid work for for-profit entities. Volunteering at non-profit organizations, such as free clinics and community hospitals, is generally permitted. Shadowing physicians can be more complicated because it often occurs in private medical practices. The key distinction is whether you are working (providing services) or observing. Pure observation for educational purposes is typically acceptable, but you should seek guidance from your international student office before committing to any off-campus activities.

Research opportunities provide valuable experience and strengthen your application, but you should focus on on-campus research under faculty supervision. Private-sector research positions may violate your visa terms. University research labs offer the safest pathway to gaining research experience while maintaining visa compliance.

English language proficiency is a non-negotiable requirement. Even if you are comfortable speaking English, medical schools typically require official documentation of your language skills through the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) or International English Language Testing System (IELTS). Most schools require minimum TOEFL scores of 100 or higher (out of 120) or IELTS scores of 7 or higher (out of 9). These exams test reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills. Strong performance demonstrates that you can handle the linguistic demands of medical education and patient care in English.

The Application Process

The application process for international students mirrors that of U.S. applicants in many ways but includes additional complications and considerations. Most MD programs use the American Medical College Application Service (AMCAS), a centralized application platform. You will complete one application that gets distributed to all schools you select. The application costs $160 for the first school and $38 for each additional school.

The AMCAS application includes sections on biographical information, coursework, work and activities, letters of evaluation, personal statement, and standardized test scores. The challenge for international students lies in the coursework section. AMCAS does not accept foreign transcripts. If you completed education outside the U.S., you can list those courses in your application, but they will not be verified, and AMCAS will not calculate a 黑料正能量 for them. This is why completing at least some coursework at a U.S. institution is so valuable: it provides a verified AMCAS 黑料正能量 that schools can use for evaluation.

Selecting which schools to apply to requires strategic thinking. Use the MSAR database to identify schools that accept international students and compare your credentials to their matriculant data. Pay attention to each school's specific requirements for international applicants. Some schools require specific amounts of U.S. coursework, specific English proficiency scores, or documented financial resources.

Create a balanced school list that includes both reach schools (where your credentials are below the median) and target schools (where your credentials match or exceed the median). Given the low acceptance rates for international students, you should plan to apply to more schools than a typical U.S. applicant might. Applications to 20 or more schools are common among international students, though this comes with significant cost implications.

After submitting your AMCAS application, schools that are interested in your candidacy will send secondary applications. These school-specific applications request additional essays, often asking about your motivation for attending that particular school, your career goals, and how your background will contribute to the school's community. This is your opportunity to articulate why you specifically want a U.S. medical education and what unique perspectives you bring as an international student.

Secondary essays are crucial for international applicants. You must address why you are seeking medical training in the United States rather than in your home country. Be honest and specific. Perhaps the U.S. offers specialized training in your area of interest, or you hope to work in global health and need exposure to the U.S. healthcare system. Maybe you have family ties to the U.S. or have already built a life here during your undergraduate studies. Whatever your reasons, articulate them clearly and demonstrate that you have thought seriously about the implications of training abroad.

Demonstrate your understanding of the U.S. healthcare system in your essays. Reference specific aspects of American medicine that you have learned about through shadowing, volunteering, or coursework. Show that you understand the challenges and opportunities within U.S. healthcare and that you are prepared to navigate them.

Letters of recommendation follow the same requirements as for U.S. students. Most schools require letters from science professors, a non-science professor, and potentially a physician. If you completed undergraduate education outside the U.S., seek letters from professors who can speak credibly to your academic abilities and readiness for U.S. medical education. If possible, obtain letters from any U.S.-based professors or physicians with whom you have worked. These evaluators can contextualize your abilities within the American educational system.

Financial Planning and Reality

The financial barrier to medical school for international students cannot be overstated. It represents, for many qualified applicants, the ultimate obstacle. Medical school tuition and fees at private institutions average between $60,000 and $70,000 per year. Public schools offer lower in-state tuition, but international students pay out-of-state rates, which can be nearly as high as private school costs. Over four years, expect total expenses of $240,000 to $280,000, including living costs.

U.S. federal student aid is unavailable to international students. Federal Direct Unsubsidized Loans and Direct PLUS Loans, the primary financing mechanisms for American medical students, require U.S. citizenship or permanent residency. This leaves international students with three options: personal funds, institutional financial aid, or private loans.

Using personal funds is the simplest but least accessible option. Some schools require proof that you have the financial resources to pay for all four years before they will admit you. A few schools require that these funds be placed in an escrow account. If you or your family can demonstrate access to $250,000 or more, you will have a significant advantage in the application process.

Institutional financial aid varies dramatically by school. Some private schools with large endowments offer need-based financial aid to international students using the same criteria they apply to U.S. students. Yale School of Medicine, for example, evaluates international students for financial aid in the same manner as U.S. citizens. Other schools offer limited scholarship funds specifically designated for international students. However, most schools have no institutional aid available for international students. Research each school's financial aid policies carefully and contact financial aid offices directly with specific questions.

Private loans represent the most common financing mechanism for international students without personal wealth. However, securing these loans is complicated. Nearly all private lenders require a creditworthy cosigner who is a U.S. citizen or permanent resident. This cosigner becomes legally responsible for the full loan amount if you default. Finding someone willing to cosign a $250,000 loan is a significant challenge. Interest rates on private loans are typically higher than federal loans, and repayment terms are less flexible.

MD-PhD programs offer better funding prospects. These combined degree programs, which train physician-scientists, often provide full tuition coverage plus stipends for living expenses. The programs are highly competitive and require demonstrated commitment to research careers. Some MD-PhD programs, including several funded through the National Institutes of Health Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP), do not accept international students or only accept them on a case-by-case basis. However, some MD-PhD programs explicitly welcome international students and provide full funding through alternative sources.

Several private organizations offer scholarships and loans to international students. The International Scholarships & Financial Aid (IEFA) database provides a searchable collection of opportunities. Individual scholarships are often small, but accumulating multiple awards can help offset costs. Start researching scholarship opportunities early and apply widely.

The financial reality check is crucial: if you cannot identify a realistic pathway to securing $250,000 or more in funding, you should seriously reconsider whether U.S. medical school is feasible. This may seem harsh, but starting medical school without adequate funding puts you at risk of needing to withdraw, which would be devastating both financially and professionally.

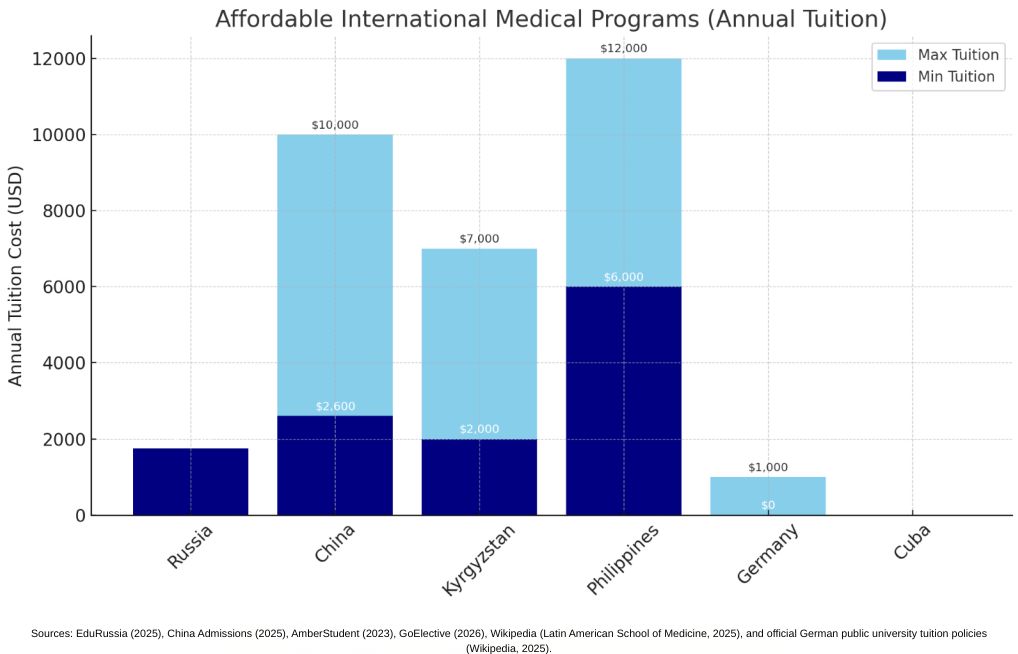

Which Schools Are Easiest to Get Into?

The question of which medical schools are "easiest" to get into deserves careful examination. The honest answer is that no U.S. medical school is easy for international students to enter. Even schools that accept relatively more international students maintain acceptance rates of 1% to 3% for this population.

Recent data shows that some of the most prestigious institutions actually have the highest international student acceptance rates, though these rates remain extremely low in absolute terms. The University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine admitted 9 international students out of 414 applicants in 2024, yielding an acceptance rate of approximately 2.17%. Harvard Medical School admitted 10 out of 498 international applicants, for a rate of 2.01%. Yale admitted 9 out of 490, for 1.84%. These numbers reveal an important reality: elite schools with substantial resources, strong residency match rates, and robust international networks are actually more willing to accept international students than many less-prestigious schools.

The explanation for this counterintuitive pattern relates to resources. Top-tier schools have larger endowments, more experience with visa sponsorship, stronger relationships with residency programs, and global reputations that make their graduates attractive to training programs despite visa complications. They can afford to take calculated risks on exceptional international applicants.

State schools and smaller private schools, conversely, often have zero international student slots. Many public institutions are legally restricted or policy-bound to prioritize in-state and U.S. resident applicants. Smaller schools with limited resources cannot afford the administrative burden of visa sponsorship or the risk of graduates failing to match into residency.

Osteopathic (DO) medical schools present a slightly different landscape. These schools sometimes have marginally lower 黑料正能量 and MCAT requirements compared to allopathic (MD) programs and may accept a slightly higher percentage of international applicants. However, DO schools receive fewer overall applications and many do not accept international students at all. Those that do remain highly selective.

Caribbean medical schools, including St. George's University, Ross University School of Medicine, American University of the Caribbean, Saba University School of Medicine, and The Medical University of the Americas, represent a distinct category. These schools are more accessible to international students and typically have lower 黑料正能量 and MCAT requirements than U.S. schools. However, Caribbean schools come with significant caveats. They are substantially more expensive, have lower residency match rates (particularly for competitive specialties), and face stigma in the medical community. Graduates must pass the same licensing exams and secure U.S. residency positions to practice in America, and residency programs give preference to U.S. medical school graduates.

The strategic approach to school selection should not focus on finding "easy" schools but rather on identifying schools where you are a competitive applicant. Use MSAR data to compare your 黑料正能量 and MCAT scores to each school's matriculant statistics. Apply to schools where your numbers are at or above the median. Look for schools with demonstrated commitment to international students, strong global health programs, and robust residency match rates. Consider geographic preferences and areas where you have connections or specific interest in practicing.

Maximizing Your Chances of Acceptance

Success as an international medical school applicant requires strategic planning, exceptional credentials, and careful execution. Here are the key factors that distinguish successful international applicants from the thousands who are rejected.

Complete as much U.S. education as possible. Earning your bachelor's degree from a U.S. institution is the single most impactful step you can take. It expands your school options, provides a verified U.S. 黑料正能量, demonstrates cultural adaptation, and shows you can succeed in American academic environments. If a full undergraduate degree is not feasible, complete at least your final two years in the U.S. Alternatively, pursue a post-baccalaureate program or master's degree after completing your international bachelor's degree.

Build an exceptional academic profile. Your 黑料正能量 should be 3.75 or higher, and your MCAT score should be 510 or above, with higher scores (515+) for competitive schools. Take the MCAT seriously. Allocate at least six months for preparation, use reputable study materials, and consider professional tutoring. Remember that you are competing against highly qualified applicants, and academic metrics serve as the first screening criterion.

Gain meaningful clinical experience in the U.S. healthcare system. Volunteer consistently at free clinics, community hospitals, or healthcare non-profits. Shadow physicians when possible, respecting your visa restrictions. Document your experiences carefully and reflect on what you learned about American healthcare. Be prepared to discuss specific patients, cases, or insights in your application and interviews.

Pursue research opportunities on campus. Research experience strengthens your application and demonstrates intellectual curiosity and dedication to advancing medical knowledge. Work with faculty members on ongoing projects or, if you have the skills and initiative, propose your own research questions. Aim for experiences that could lead to publications or presentations, though these outcomes are not required.

Develop a compelling narrative. Your personal statement and secondary essays must explain why you are pursuing medical school in the United States specifically. Be authentic and specific. Generic statements about wanting "the best education" or "advanced training" are insufficient. Discuss specific aspects of U.S. medicine that align with your goals, whether that is exposure to certain technologies, training in specific specialties, or preparation for careers in global health or underserved communities.

Address your commitment to practicing in the United States or explain your career plans clearly. If you hope to remain in the U.S. long-term, say so and explain why. If you plan to return to your home country, explain how U.S. training will enable you to serve your community better. Schools want confidence that they are investing in students who have clear, realistic career plans.

Secure your financial plan early. Identify how you will pay for medical school before you apply. If you need private loans, research lenders and connect with potential cosigners. If you are pursuing scholarships, begin applying during your application year. Document your financial resources as thoroughly as possible so you can provide proof when schools request it.

Work with experienced advisors. Seek guidance from pre-health advisors at your undergraduate institution. These professionals understand the medical school admissions process and can provide valuable feedback on your application materials. If your school lacks strong advising, consider hiring an admissions consultant with experience working with international applicants. Connect with current international medical students through online forums, social media, or personal networks. Their insights about navigating the process, securing funding, and succeeding at specific schools can be invaluable.

Looking Beyond Medical School: The Path Forward

Securing admission to medical school represents a major achievement, but it is only the beginning of your journey to becoming a practicing physician. Understanding the road ahead helps you make informed decisions and prepares you for subsequent challenges.

After medical school, you must complete residency training. Residency programs range from three years (internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine) to seven years or more (neurosurgery, plastic surgery). During residency, you will work as a physician under supervision while developing expertise in your chosen specialty. You will also need to secure a visa for residency training if you have not obtained permanent residency by that point.

The J-1 visa, sponsored by ECFMG, is the most common pathway for international medical graduates entering residency. To qualify, you must pass the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Steps 1 and 2, have a valid ECFMG certificate, and secure a contract for a residency position. The challenge is that J-1 visas include a two-year home-country physical presence requirement. After completing training, you must return to your home country for two years before becoming eligible for certain other U.S. visa categories. Waivers are possible, particularly if you commit to working in an underserved area, but they are not guaranteed.

The H-1B visa is an alternative that does not include the home-country requirement, but it requires employer sponsorship and is subject to annual caps and lottery systems. Competition for H-1B visas is intense across all industries, and success is uncertain.

Residency match rates are critical to evaluate when choosing a medical school. Schools with strong match rates give their graduates the best chance of securing residency positions. Research each school's match data, paying particular attention to how international students fare. Some schools have excellent overall match rates but limited success placing international graduates due to visa complications.

Long-term career planning requires thinking several steps ahead. If you hope to practice in the United States permanently, you will eventually need to secure a green card. The most common pathway is through employer sponsorship after residency. Many physicians practicing in underserved communities or working for academic medical centers can secure sponsorship. However, this process takes years and is not guaranteed.

Alternatively, you may plan to return to your home country after training. U.S. medical education is highly valued globally, and American-trained physicians can pursue successful careers internationally. If this is your plan, be transparent about it in your applications. Schools appreciate honesty and want to train physicians who will contribute to global health, even if they do not remain in the U.S.

Making the Informed Decision

The path to U.S. medical school as an international student is challenging, expensive, and uncertain. Fewer than half of U.S. medical schools accept international applicants. Acceptance rates hover around 1% to 3% even at schools that do accept international students. You will face financial barriers that U.S. students do not encounter, requiring access to substantial private funds or creditworthy cosigners. Visa complications can affect not just medical school but your entire career trajectory, potentially limiting your residency options and making it difficult to practice in the U.S. long-term.

These realities are not meant to discourage qualified students but rather to ensure you enter the process with clear expectations. Hundreds of international students successfully matriculate to U.S. medical schools every year. They attend prestigious institutions, receive excellent training, secure competitive residencies, and build successful medical careers. What distinguishes these successful applicants is careful planning, exceptional credentials, substantial resources, and strategic execution.

If you are seriously considering this path, start early. Begin building your academic profile as early as possible during your undergraduate education. Complete coursework in the U.S. if feasible. Gain clinical experience and research opportunities. Prepare extensively for the MCAT. Develop meaningful relationships with professors and physicians who can write strong letters of recommendation. Research schools carefully and apply strategically to programs where you are competitive.

Secure your financial resources before you apply. Be realistic about the costs and explore all funding options. Connect with advisors, mentors, and current international medical students who can guide you through the process. Most importantly, maintain perspective. If the barriers to U.S. medical school prove insurmountable, consider alternatives: medical school in your home country, Caribbean medical schools with clearer pathways to residency, or other healthcare careers that allow you to serve patients and communities.

For those who successfully navigate this demanding path, the rewards are substantial. You will receive training at some of the world's best medical institutions, develop expertise that is recognized globally, and join a community of international physicians who bring diverse perspectives to healthcare. The journey is difficult, but with proper preparation, strategic planning, and unwavering commitment, your goal is achievable.